When I interviewed for my job at Carleton University way back in 1999, I had a private meeting with a faculty member. They asked me a question: can you name an academic whose career you see as a model for your own?

Holy moly, I thought, what an easy answer.

“Peter Russell,” I said.

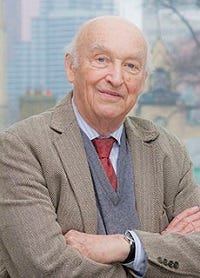

I want to immediately acknowledge my privilege as a young white guy answering that question, as I had quite a lot of old white guys to choose from as career models. Still, there was something special about Peter Russell, a professor of political science at the University of Toronto who died earlier this week at the age of 91.

The title of Peter’s 1997 retirement festschrift is Ideas in Action, and that captured him well. He was an accomplished academic who seemed to wear nothing except shades of brown. But he had a truckload of additional professional distinctions and moved easily in the halls of power. Some speak of the “Laurentian Elite,” and if it exists, Peter was at the top of that heap. Even as I write this, the tributes are poring in from the prominent and powerful.

Peter was interested in the interplay of political institutions, power, and people. I’m not going to go into a long treatise on his sprawling body of academic work. But he embodied, and to significant extent built, a very Canadian tradition.

In political science, there was once a very traditional field studying the rules and structures of institutions. This was later supplanted by “neo-institutionalists” in the 80s, and further variations like “historical institutionalists” since. Though he sure studied institutions, Peter never quite fit into any of those categories. Rather, he was what I can only call a Canadian institutionalist. He was fundamentally motivated to understand how institutions worked and affected political outcomes; but also how people interacted with them; and ultimately how they could work better. In the early 2000s Miriam Smith wrote a stellar analysis* of this “unique English Canadian institutionalist tradition,” and while she doesn’t specifically mention Peter, he was deeply part of it, with a particular contribution of bridging law and politics. And it is fundamentally the tradition that I follow as well.

I knew Peter for thirty years, though solely on a professional basis; I would not presume to say we were friends, nor were we ever working colleagues or collaborators. But he was a Presence, in both a scholarly and personal way, and loyal to our shared academic home of the Canadian Political Science Association. He showed up to things (I believe he holds the all-time record for attendance at the CPSA annual meetings, though not consecutively). He wrote in a very approachable style. And he always spoke with vigour, in his slightly gruff but engaging manner. Most of all, he engaged easily with those younger than him. One of my last pre-pandemic memories of time with Peter was at a hotel bar in Regina in 2018, after the CPSA presidential dinner where his book Canada’s Odyssey won the Donald Smiley prize for the best book in Canadian politics that year. Peter was just hanging out with a few people, of which I think I was the next oldest, and having a great time.

Peter was a person of privilege; coming from what I understand to be a comfortable Toronto background, he was not even “Dr Russell”; he never earned a PhD and was hired on the basis of his first at Oxford. Like others in his position (and me), he was able to study and interpret the institutions of privileged white men in part because he was one himself. But one thing I greatly admired about him was his interest in new things and capacity for growth. And his focus increasingly went well beyond institutions; more and more - and really in some sense always - it was all about people.

I didn’t always agree with Peter. I failed to fully share his enthusiasm for minority governments and devotion to electoral reform, and I felt he was excessive in his criticisms of Stephen Harper. I saw him say and do some clunky things, one of which I had to later repair. But I fundamentally admired Peter Russell, and still do. He’s still my answer to that question, and I will miss him.