Independents, and Independent Independents

How can non-affiliated legislators be appropriately included in proceedings?

Earlier today I appeared before the Senate Committee on Rules, Procedures and the Rights of Parliament to talk about how different Canadian legislatures treat independent members. The Senate is reviewing its approach to “non-affiliated” senators who are not part of an organized party or group, even the Independent Senators Group. This was a fun - well, fun in my view - opportunity to do some quick research and thinking on the subject.

Independents are of course rare in Canada. Apart from the Senate, there are three main types:

Elected Independents. Members elected under an independent banner. Jody Wilson-Raybould is the last for the House of Commons in 2019. There are currently two such MHAs in Newfoundland and Labrador, one MLA in Nova Scotia (pending today’s election results), and one MPP in Ontario.

Formerly Affiliated Members. Members who have left their party for voluntary or involuntary reasons, but have not yet faced re-election. This is the most common type of non-affiliated member, though the reasons for their departure vary widely, from policy disagreements to personal misconduct. The Ontario Legislative Assembly alone has five such MPPs at the moment; Quebec has three MNAs; Manitoba has one MLA; and the House of Commons has three MPs, along with the special case of Pablo Rodriguez who left the federal Liberals in good standing and is running for the Quebec Liberal leadership.

No Party Recognition. Members elected under the label of a party that does not have sufficient seats to be recognized under the legislature’s rules, such as the two current Green MPs. These aren’t really “independents,” but are stuck in a special limbo category due to their lack of official party status. The lone current Liberal MLA in Manitoba, Cindy Lamoureux, is another example.

There’s some further variations here, such as MP Kevin Vuong, who was elected in 2021 under the Liberal label but after the party had disavowed him mid-campaign, so he entered the House as an independent. In fact, pretty much everyone in #1 and #2 above has their own unique story of how they became independents, and that can influence both how they are treated and what they seek. For example, Mr Vuong has made no secret that he wants to join the Conservatives, but they aren’t very interested. Alberta also recently saw a quasi-independent, Jennifer Johnson, who was elected in 2023 under the United Conservative banner but was not allowed to join the UCP caucus until recently because of transphobic comments. On the other hand, Bobby Ann Brady was elected as an independent in Ontario in 2022 with the support of the local Progressive Conservative establishment but has not made friends with Doug Ford. Again, every independent has their own unique story.

[Interesting side-observation warranting future analysis; while it’s a small pool at any given time, independents split about equally between men and women; given their overall underepresentation, this suggests women are more likely to be/become independents, though most members expelled from their parties for misconduct are men.]

What about the Senate? Even in the new independently-appointed Senate, there are senators who want to be, well, independent independents who have not joined any of the Senate’s four entities: the Conservatives, the Independent Senators Group, the Progressive Senators Group, and the Canadian Senators Group. There are technically eleven “non-affiliated” senators right now, though this includes the Speaker and the three Government Representative Office senators, as well as some brand new senators who may not have yet chosen a group. But there’s a few that have clearly chosen to not be affiliated, and three of them appeared before the rules committee in June to plead that they were “second-class” and needed to “beg for scraps” because of their status.

Indeed, all legislative business runs primarily through parties (and/or “groups” in the case of the new Senate). But independents, regardless of their background story, are still duly-elected/appointed members. So how can legislatures reasonably accommodate independent/non-affiliated members in their proceedings?

My view, which I think should be uncontroversial, is the principle that independents should have proportionately similar opportunities to that of a typical ordinary member or backbencher in a party/group - i.e, similar opportunities to speak in debate, to make statements, pose questions, pursue private members legislation, participate in committees, etc. That’s the principle. The problem is calculating and applying it.

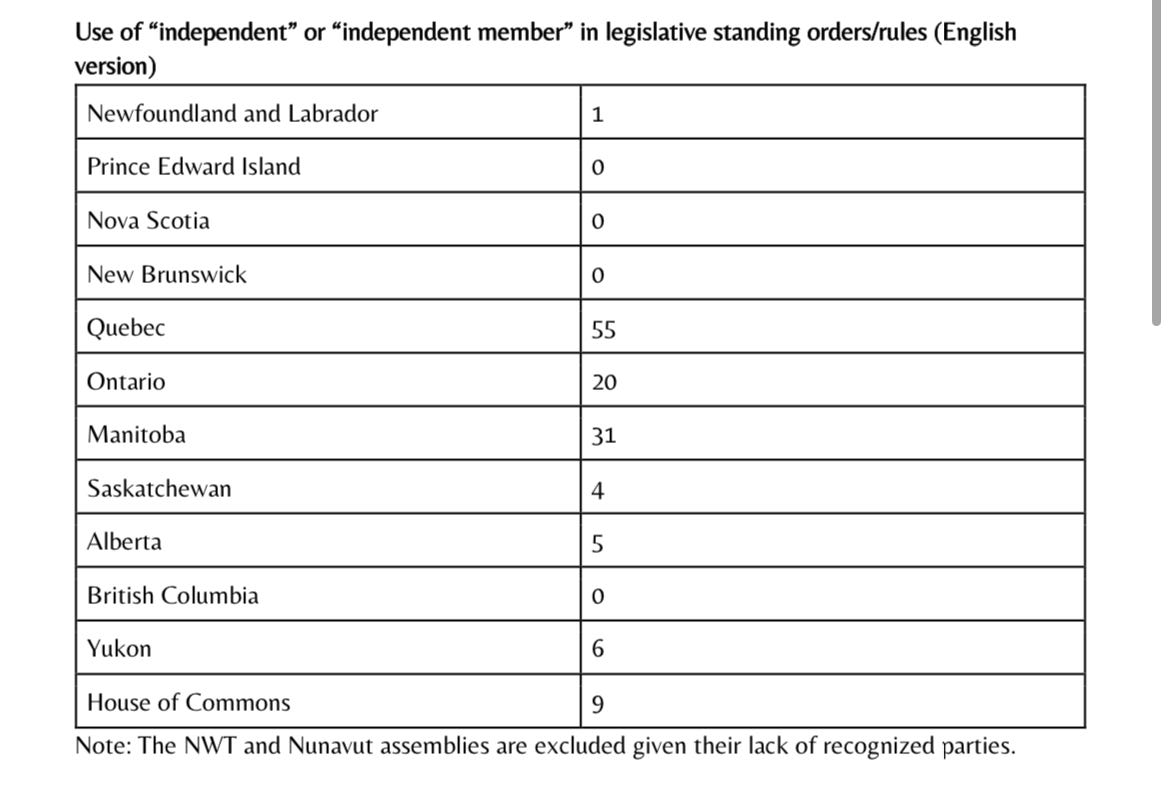

There are two broad approaches to accommodating independent members, and they can be illustrated in a crude but effective way simply by searching each legislature’s standing orders for the word “independent.” Check this out:

Do these wide variations suggest Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba are generous to independents while BC and the Maritimes don’t do a thing for them? Not necessarily; my rudimentary exercise simply suggests the extent to which legislatures have codified their procedures to include independents. The other option is to be flexible, leaving accommodations up to the Speaker and/or the organized parties to grant occasional opportunities for independents. A good account of this ad hoc approach is Vicki Huntington’s description of the accommodations made for her - or not made for her - as an elected independent in British Columbia in 2009.

In fact we’ve got a classic Canadian constitutional question here: is it better to have written rules for clarity, or to keep things unwritten and flexible? I’m going with the classic Canadian answer: maybe/both/it depends.

The difficulty with codifying rules for independents is that it is difficult to anticipate all scenarios, and codification could be seen as giving them special privileges not available to the average party backbencher. After all, backbenchers have their own complaints about being second class and forgotten. On the other hand, leaving things to the discretion of the Speaker and others puts independents in a subservient and dependent position; “begging for scraps” as one senator said at the June hearings. (But then, party backbenchers often say the same.)

Let’s also be frank: the motivation to help varies. Let’s say it again: every independent has their own story. If they left because of misconduct or controversial behavior, no one feels hugely motivated to lift a finger for them. If they broke from their party over policy disagreements, their former party won’t be very warm to them; but other parties might, though for instrumental rather than altruistic reasons. Similarly, independents may seek different things. Some are hoping to be adopted by a party and will closely hitch themselves to that wagon; some are mavericks not particularly interested in working with anyone; some are frankly invisible and don’t seem to really care, knowing their political career is on its last legs, since very few independents are re-elected.

But that last point isn’t applicable in the appointed Senate. Instead, there is a seemingly permanent class of independent independent - er, “non-affilated” senators, and this brings me back to the beginning; the Senate is trying to figure out the best approach for them and whether any changes to its current rules are warranted. The good news, as I told senators, is that the Senate has long been a more collegial chamber than the House or provincial legislatures; less frantic and less of a zero-sum game of ‘I only win if you lose,” even before the changes of 2016. This more collegial game hopefully sets it up well to accommodate its special class of independent independents through a mix of written rules and unwritten flexibility. But overall, since independent legislators in Canada are rare and each has their own story, there will never be a single clear solution for accommodating them.